Building on previous work [1], we proposed [2] a novel approach for building a generative model using a nonnegative tensor tree and demonstrated its ability to capture the hidden structure of various synthetic and real-world datasets. Machine learning models based on tensor networks typically use a Born machine ansatz, where the wavefunction is directly modeled and the probability of a given sample is determined by squaring the wavefunction (the Born rule). However, in this scheme, we cannot directly interpret the model since it is a type of quantum model.

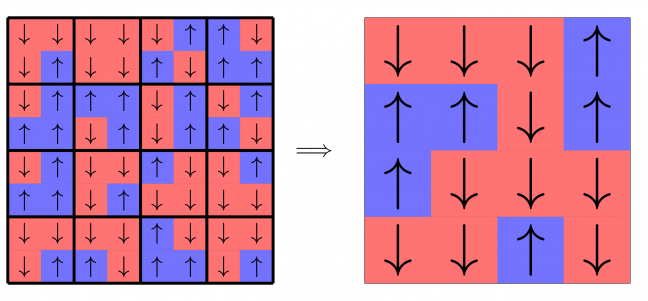

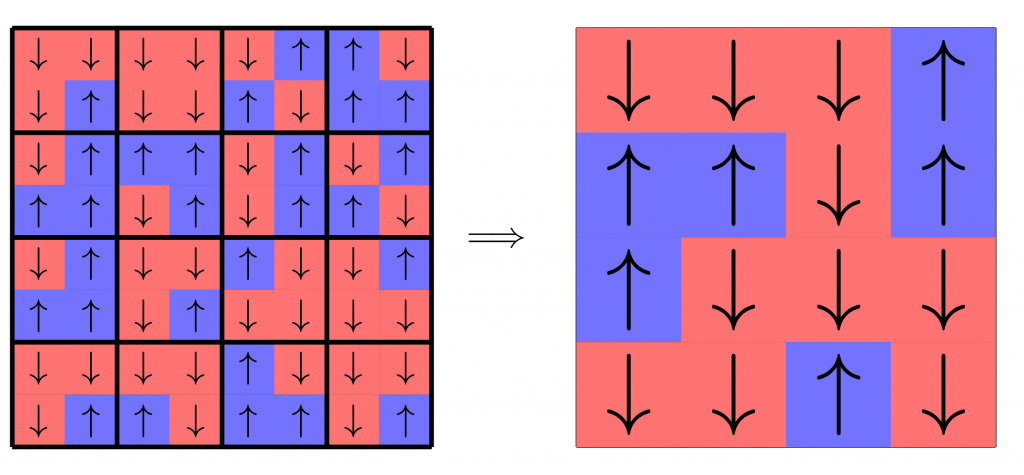

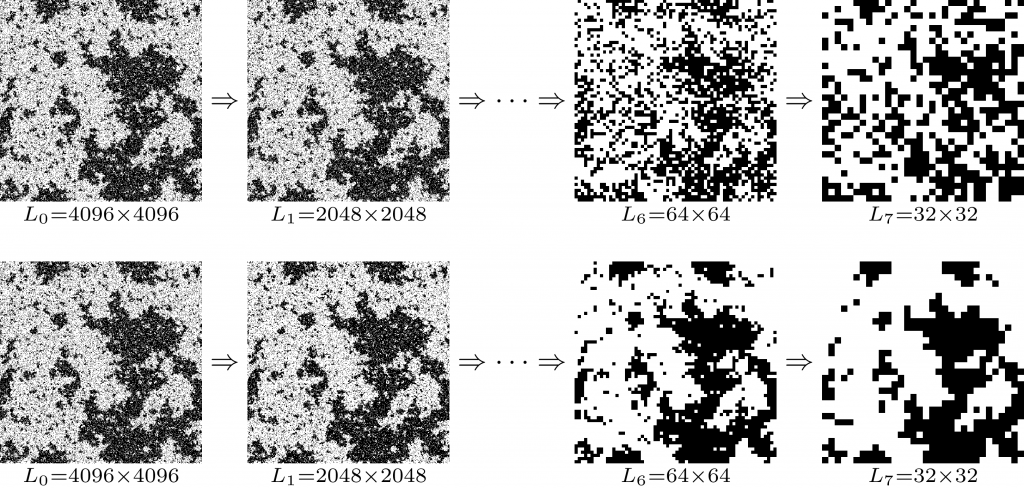

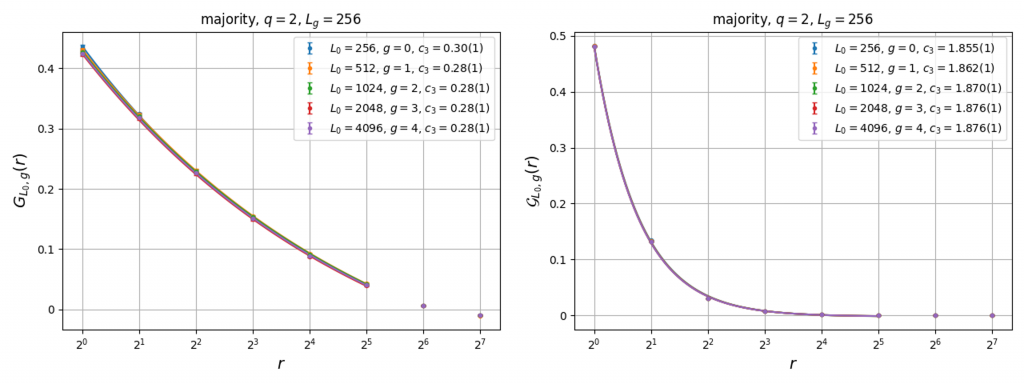

In our work [2], we considered an adaptive tensor tree constrained to have nonnegative elements. We showed that there is an equivalence between our proposed model and hidden Markov models, and that this establishes a basis for the probabilistic interpretation of our proposed model, which we call a “nonnegative adaptive tensor tree” (NATT). We call the tensor tree an adaptive tensor tree because it can change its structure according to the training data. We perform local rearrangements of the network structure favoring

To demonstrate a concrete application of our method, we consider real data drawn from bioinformatics, where we reconstruct a cladogram of species in the taxonomic family Carnivora (dogs, cats, and related species) using mitochondrial DNA sequence data from a specific gene common to all the considered organisms. We found that the resulting network showed a generally correct hierarchical clustering of species even if the only information provided was unlabeled DNA sequence alignment data. The figure shows an example network structure generated using our method. Our method correctly determines the hidden structure of the data by clustering similar species based entirely on genetic information. The advantage of our method is in the observation that the network structure and weights correspond to a probabilistic model that describes the mutation of nucleotides, which means that the generated tensor tree is fully interpretable as a model of a stochastic process. We expect that the NATT would be a useful tool in exploratory data science applications and transparent AI, where developing interpretable generative models for large datasets containing hidden correlation structures is of particular interest.

[2] Katsuya O. Akamatsu, Kenji Harada, Tsuyoshi Okubo and Naoki Kawashima, “Plastic tensor networks for interpretable generative modeling”, Mach. Learn.: Sci. Technol. 7 (2026) 015014.

(https://doi.org/10.1088/2632-2153/ae3048)